This article is part of a series. Next week, I’ll release a short report on digital learning.

The arguably most studied problem in education is how to conduct education. Whenever someone provides education, this necessarily involves thinking about how to bring across the material at hand.

Education has not changed meaningfully over the course of human history. Whether in Plato’s Academy back in Ancient Greece or in schools nowadays, teaching usually means the transfer of knowledge from a teacher to students.

How does learning work then, what makes it efficient, and what are the opportunities for digital technologies?

Cognitive Load Theory

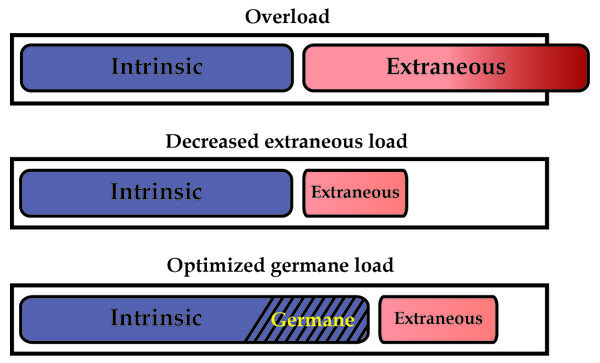

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) is one of the most prominent learning theories, to explain learning. This theory claims that the processing power of our brains is constrained, just as in computers. Learning is most effective if cognitive load matches the learner’s limited mental capacity.

CLT differentiates intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load:

Intrinsic cognitive load describes the inherent difficulty of learning material. It cannot be reduced, but can be managed. For example, language learning brings together many new concepts, a high intrinsic load. By focusing on select aspects, intrinsic load can be managed.

Extraneous cognitive load refers to the unnecessary burden in the presentation of the learning material. For example, phones in the proximity of our learning environment can be distracting, creating unnecessary extraneous load. This load adds to the intrinsic load, and can easily overload the mental capacity. Extraneous load should be kept to a minimum for effective learning, e.g. by adapting the style of learning and teaching.

Germane cognitive load characterises the cognitive load devoted to processing of learning material, and integrating it into new schemes. Teachers can promote germane load to improve learning.

Mental Schemes

Since our mental capacity is limited, learning works by building ‘schemes’ in our heads. These schemes are connections between old and new knowledge. Built schemes in our minds allow to reduce cognitive load in subsequent tasks.

This is why mathematics classes start with the basics, and introduce ever more involved concepts. One concept builds upon another, but by continuous effort we (hopefully) get familiar with the material, and learn the big picture.

Over time, learning material gets easier for the learner, and intrinsic load decreases. If we ever go back to what we learned in the past, we will find things much easier (unless we’ve completely forgotten..). This underlines how intrinsic load always depends on the 1) the cognitive abilities of the learning, and 2) the familiarity of the learner with a subject.

Lessons for Digital Learning

In digital learning, teachers often structure learning content in short videos, instead of lengthy lectures. This shall direct the learner’s attention to the learning material.

There’s a fine balance (see also figure below). If the learning units are too short, cognitive load might be too little. Forming schemes is difficult from many separate pieces. Substantial effort must be spent on putting pieces together (limited germane load). The user interface of learning tools can itself impede learning efforts, and cause friction in learning (extraneous load).

A one-fits-all solution to teaching will never exist. Instead, learning is individual, to which teaching must adapt. Offline teaching, with its high level of adaptability, will continue to exist.

Further reading:

- A nice overview of CLT in the context of language learning

- John Sweller and others: ‘Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later’