This article was written for the Inspired Research magazine of the Depatment of Computer Science of the University of Oxford. URL: https://www.cs.ox.ac.uk/innovation/inspiredresearch/InspiredResearch–summer23_FINAL_web.pdf

Tracking, the collection and sharing of behavioural data about individuals, is widely used by app developers to analyse and optimise apps and to show ads. It also is a significant and ubiquitous threat in mobile apps, and often violates data protection and privacy laws.

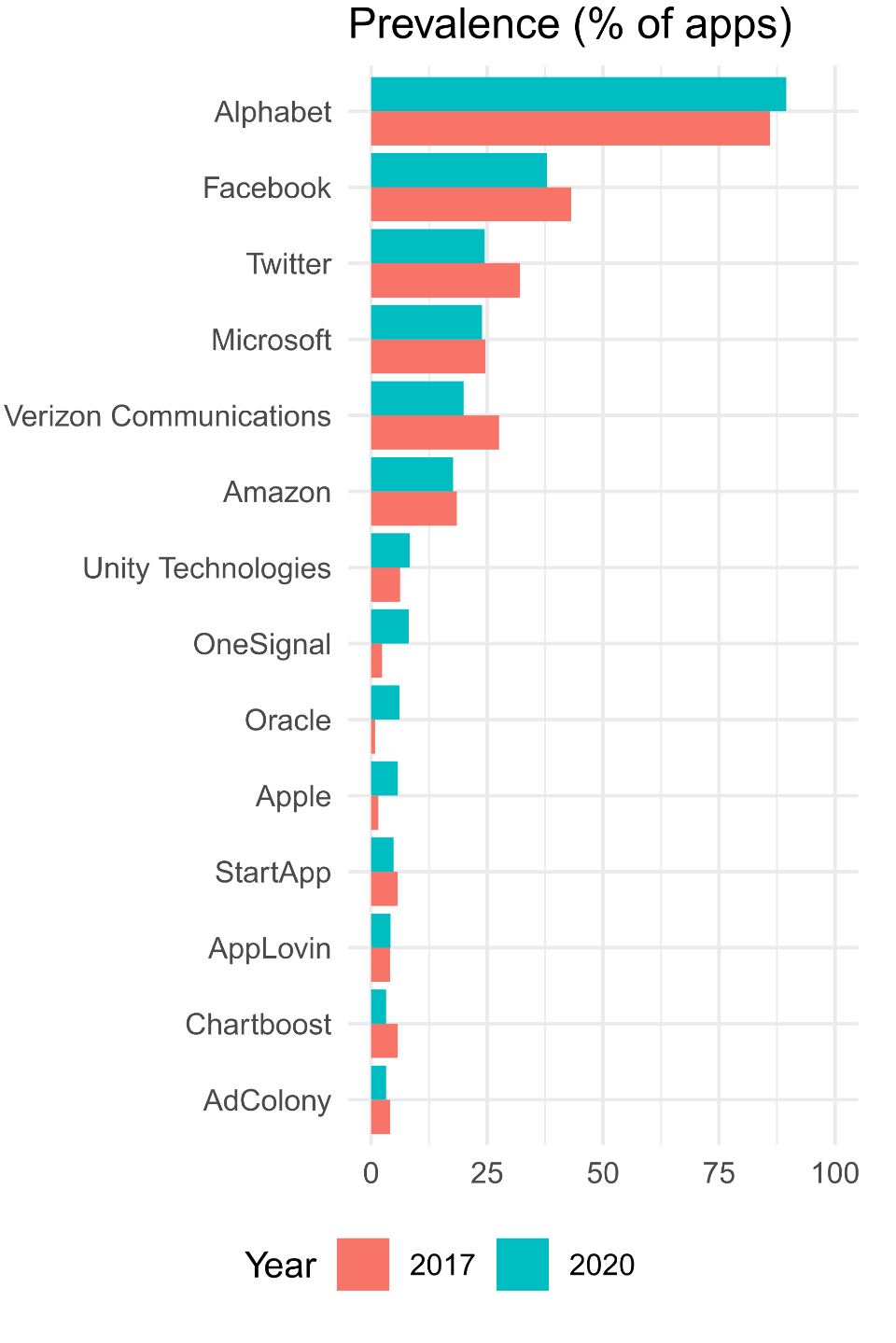

Previously, our research group led by Prof Sir Nigel Shadbolt analysed 1 million Android apps from the Google Play Store from 2017. We found that about 90% of those apps could share data with Alphabet (the parent company of Google), and 40% with Facebook (now renamed ‘Meta’). The data practices in children’s apps were particularly worrisome, which is why our research group – in response – established a dedicated research strand on Kids Online Anonymity & Lifelong Autonomy (KOALA), led by Dr Jun Zhao. Our findings led to major news coverage back then (including by the Financial Times). This underlines the extent to which those data practices violated individuals’ privacy expectations. Google even issued a public response to our findings, in which they tried to cast doubt over the validity of our (peer-reviewed) methodology.

The much-debated General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into force in the EU and UK in May 2018. This new law aimed to protect personal data better than its predecessor, the Data Protection Directive (DPD) from 1995. Compared to the DPD, the GDPR introduces significant challenges for compliance in the context of tracking, particularly through higher potential fines (up to £17.5 million or 4% of global annual turnover), better regulatory alignment and enforcement and a higher bar for consent. Since there existed (and still exist) rather limited empirical insights into the extent to which the law achieved its intended aims, we set out to replicate the same analysis of Android apps several years later. Interestingly, compared to our previous study, our renewed work attracted much less public attention, which may underline that many of us have become used to invasive and illegal data practices by tech giants over the past few years.

Method. We analysed 2 million apps from the UK Google Play Store, 1 million apps from 2017 and 1 million from 2020. We performed an automated scan of apps’ code to identify all domains that are known to belong to tracking companies, thereby characterising the companies that apps can potentially send personal data to. If there have been changes in the extent of tracking following the introduction of the GDPR, we should expect that they show up in our results. Crucially, we did not investigate what kinds of data were shared by apps, since machine learning approaches (commonly referred to as “AI”) nowadays make it possible to get detailed insights into the lives of individuals even from seemingly benign data.

Results. Our results suggest that the GDPR has not had a large effect on the presence of tracking in apps on the UK Google Play Store. For instance, 85% of apps from 2017 could send data to Alphabet, compared to 89% in 2020. 43% could send data to Facebook in 2017, and 38% in 2020. Apps, on average, contain a similar number of trackers as before (5 companies in the median app). A consistent percentage of apps (15%) contain more than ten tracker companies.

Our analysis hints at a high level of concentration in the tracking market. Alphabet/Google and Meta/Facebook continue to dominate app tracking. This dominance might allow them to extract disproportionate profits from their digital advertising models, which would – in turn – increase the prices of consumer products. This dominance is currently subject to ongoing investigations by courts and authorities across the globe. At the same time, many relatively smaller companies are involved in app tracking. These smaller companies usually focus exclusively on mobile advertising, instead of having a broad portfolio of digital services like Alphabet/Google or Meta/Facebook. An important competitive advantage of these companies might be reduced public awareness and regulatory scrutiny, allowing them to compete with the market leaders at the expense of user privacy.

We further found that apps commonly shared with US-based companies. While one of the key aims of the GDPR is to facilitate the cross-border sharing of personal data between companies, the US also operate some of the most sophisticated intelligence agencies (like the NSA) and currently provide limited protections against surveillance by those agencies to non-US citizens. These practices were revealed by Edward Snowden in 2013. In light of this, the Court of Justice of the European Union repeatedly found that the US do not provide a similar level of data protection to EU citizens as the GDPR, and that personal data may usually not be sent to the US (Schrems II ruling). Apps’ ubiquitous data sharing with US companies is thus problematic, if not illegal.

Conclusions. While the GDPR is far-reaching, the law is not perfect. Apps continue to rely on invasive (and often illegal) tracking technologies. The law does not appear to have changed these incentive structures fundamentally.

Unfortunately, the GDPR remains rarely enforced in practice, which has led to a proliferation of illegal data practices online. These practices include the engagement in highly invasive data practices (including many, but not all, forms of tracking), frequent and insufficiently protected sending of personal data to the US, and also the wide adoption of annoying and ineffective consent banners.

Both the UK and EU are currently planning to revise their data protection laws. According to our broad body of research, the lack of enforcement is the central issue that needs to be addressed.

References

Binns, R., Lyngs, U., Van Kleek, M., Zhao, J., Libert, T., & Shadbolt, N. (2018). Third Party Tracking in the Mobile Ecosystem. Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3201064.3201089Kollnig, K., Binns, R., Kleek, M. V., Lyngs, U., Zhao, J., Tinsman, C., & Shadbolt, N. (2021). Before and after GDPR: Tracking in mobile apps. Internet Policy Review, 10(4). https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/and-after-gdpr-tracking-mobile-apps

2 replies on “GDPR: How a lack of enforcement came to undermine its ambition and reputation”

What would allow a similar analysis on Apple apps?

We actually did follow-up work on iOS: https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.13722

Also, I’m currently developing this: https://ios.trackercontrol.org